Post-95s players find themselves in an awkward position, once overshadowed by the glory of Messi and Ronaldo, and now forced to maintain a low profile under the relentless pressure from the emerging generation. Therefore, in the view of Oliver Kay, an author at The Athletic, if Rodri wins the Ballon d’Or this year, it will be a celebration for the post-95s players.

On October 28th, a new Ballon d’Or winner will be born at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris. It is well known that there are two main contenders for this year’s Ballon d’Or. One is Vinicius, the Brazilian winger who scored for Real Madrid in the Champions League final last season, and the other is Rodri, who has performed excellently both at Manchester City and with the Spanish national team.

If the 24-year-old Vinicius wins, he will become the first post-00s player to win the Ballon d’Or. And if Rodri wins, he will be the first post-90s player to claim the honor. Of course, regardless of who wins, they will both become the first player born after December 1987 to win the Ballon d’Or.

Perhaps only when the winner of this year’s Ballon d’Or is finally announced, can we truly consider the era of Messi and Ronaldo’s domination of the Ballon d’Or to have ended. In the past 15 Ballon d’Or awards, they have won 13 times (Messi 8 times, Ronaldo 5 times), with only the 2018 and 2022 awards going to others – Modric and Benzema, respectively.

Whether it’s Messi, Ronaldo, Modric, or Benzema, they are all players born in the 1980s. They became famous in football in their teens and reached heights that most people could only dream of in their thirties. And it is only now that they are gradually beginning to decline. The 37-year-old Messi is still the backbone of Inter Miami, while the 39-year-old Ronaldo and 36-year-old Benzema continue to play in the Saudi league. The 39-year-old Modric still holds a place at Real Madrid.

The talents of Messi and Ronaldo have overshadowed many excellent players in their thirties on the Ballon d’Or stage. Neymar, Kroos, De Bruyne, Salah, Van Dijk, Kane, Griezmann, and the retired Hazard and Bale, no matter how outstanding their performances, have never been able to surpass Messi and Ronaldo. The new generation of superstars has also emerged, with Mbappe, Vinicius, Haaland, Bellingham, Foden, Musiala, and Yamal ready to take over from Messi and Ronaldo and become the new leaders in football.

At first glance, this seems like the usual “newer generations replacing the older ones” in football. But upon closer inspection, one may wonder about the post-95s players who were born after Neymar, De Bruyne, Salah, etc., but before Mbappe, Haaland, and others. Theoretically, those born in the mid-1990s should currently be at their peak. However, in terms of fame, recognition, and their representation in top European football competitions, they cannot compare with Messi and Ronaldo, nor can they compete with players like Mbappe and Haaland.

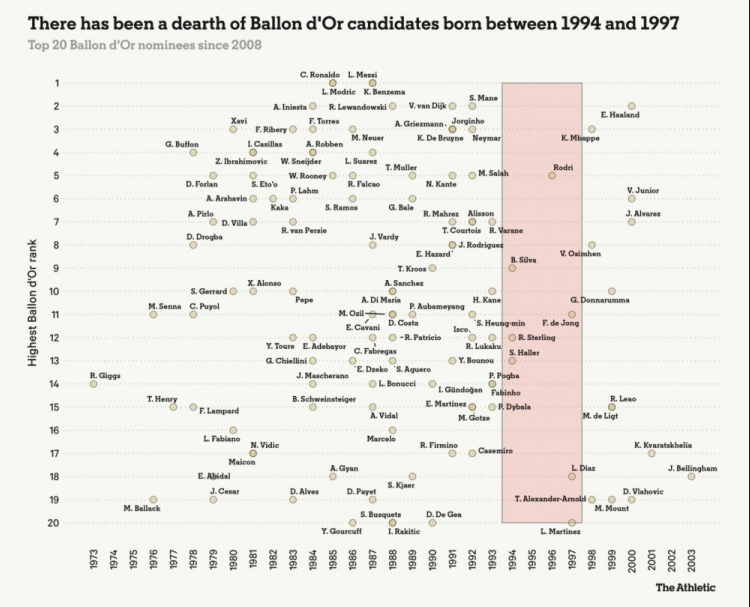

While few would consider the Ballon d’Or as the only criterion for evaluating a player’s performance, please take a look at the following chart, which shows the top 20 players in the Ballon d’Or rankings by age since 2008.

Age Distribution of the Top 20 Players in the Ballon d’Or Since 2008

Looking from the center of the chart towards both sides, you will find:

Rodri, who ranked fifth in the Ballon d’Or voting last year, is the only player born between 1994 and 1997 to make it into the top 5.

Among players of this age group, only Bernardo Silva (9th place in both 2019 and 2023) has made it into the top 10 of the Ballon d’Or, besides Rodri.

In terms of players who have made it into the top 20 of the Ballon d’Or within this age range, there are only Frenkie de Jong (11th place in 2019), Sterling (12th place in 2019, 15th place in 2021), Alei (13th place in 2022), Luis Diaz (18th place in 2022), and Lautaro (20th place in 2023).

In contrast, among the newer generation of players, Mbappe has made it into the top 10 of the Ballon d’Or for six consecutive times, while Haaland and Vinicius have done so twice, and Osimhen once.

In the 30-player candidate list for this year’s Ballon d’Or, Rodri is one of only seven players born between 1994 and 1997. The others are Ruben Dias, Hakan Calhanoglu, Dovbyk, Grimaldo, Lukman, and Lautaro, and only Ruben Dias and Lautaro have been nominated before.

Granted, this is just an award voted on by journalists and based more on subjective evaluations. But the Ballon d’Or can certainly tell you something about a player’s image and value.

In other words, the reason why there are few outstanding post-95s players is undoubtedly due to the shortcomings of this generation. In the case of Rodri and Bernardo Silva, these two players are indeed experienced and have shown outstanding performances, but the teams they play for are modern top clubs with relatively shallow historical foundations. Therefore, they also face certain disadvantages when being evaluated – for a long time, this has seemed more of an image issue than a matter of ability. This article will also explain this issue later. Besides, from a broader perspective, post-95s players seem to be striving for greater recognition – not only from fans or the media, but also from the industry.

When the FIFA Technical Study Group, led by former Arsenal manager Wenger, released its report on the 2022 World Cup, it briefly mentioned that the World Cup was “defined by the performances of young talents and seasoned masters.”

Wenger mentioned the technical and tactical abilities of Musiala, Bellingham, and Saka, as well as their tenacious mental qualities. On the other hand, he also mentioned the endurance of players in their thirties such as Messi, Ronaldo, Modric, and Giroud. He said, “In modern football, young players are ready to showcase their talents on the biggest stage earlier.” Then he shifted his attention to those players who still perform well in their thirties, adding, “This was never the case 20 years ago. It seems that the careers of high-level players have been extended.”

However, what Wenger and his technical study group did not address is that the middle-aged players, who are between the newer generation and the veterans, seem to have a relatively insufficient impact on the game. This fact is also reflected in the age distribution of players at that World Cup. Among the 832 players summoned to participate, classified by birth year, the largest number of players who took part were born in 1997 (25 years old) and 1992 (30 years old). Players born in 1994, who theoretically should have been at the best age of their careers during the 2022 World Cup, only ranked 7th in terms of the number of participants.

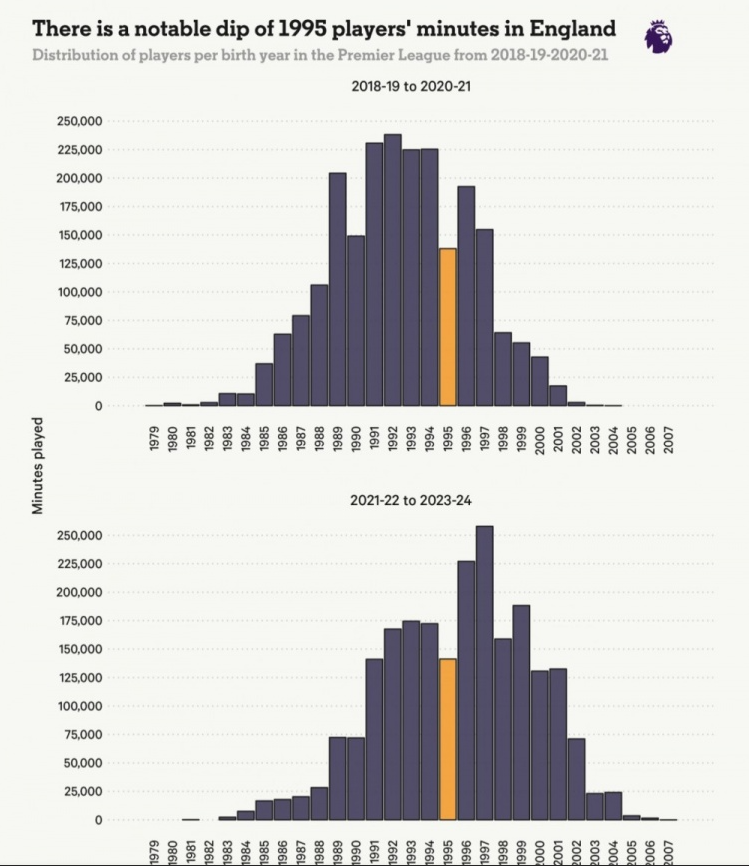

Data is cold, and numbers alone cannot directly reflect deeper meanings. However, the following chart illustrates the playing time of players of various age groups in the Premier League from the 18/19 season to the 20/21 season. The research findings are probably similar to what you have imagined: most players are concentrated in the age range of 1991 to 1994, meaning they were 23 to 27 years old at the beginning of the cycle and 26 to 30 years old at the end. In other words, these are players represented by De Bruyne, Kane, and Salah.

Players born in 1995 do not have a significant advantage in playing time in the Premier League.

Players born in 1995 have notably insufficient playing time in the Premier League. They were 23 years old at the start of the cycle and 27 years old at its end.

Perhaps this is just a coincidence and doesn’t signify much. Merely looking at this chart, you might optimistically think that the playing time for players in this age group will significantly increase in the three years following the cycle.

However, that’s not the case. Players born in 1995 did not receive more playing time in the 21/22 and 23/24 seasons (when they were 26 to 29 years old). As you might expect, the playing time for players born in the early 1990s decreased, and so did the playing time for those born between 1993 and 1995. They did not become the backbone of the team.

On the contrary, players born in 1996 and 1997 began to dominate.

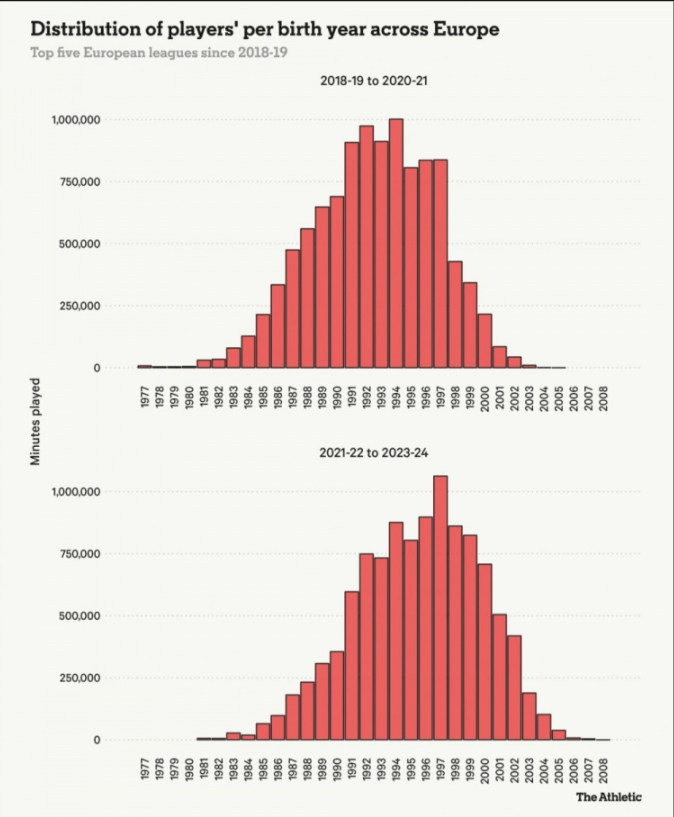

To visualize these numbers, we can look at England’s squad for the European Cup this summer. Sterling, Kalvin Phillips, Grealish, Ben Chilwell, Maddison, and Rashford, due to various reasons, were not included in the squad. They were replaced by younger players such as Anthony Gordon (born in 2001), Palmer (born in 2002), and Meenu (born in 2005). This also reflects a broader trend. Still using the aforementioned three-year cycle as the research period, the players with the most playing time in the top five European leagues have shifted from those born in the early 1990s to those born after 1997. Theoretically, the “curtain call” for players born in the early 1990s should have paved the way for those born after 1995 to take on leading roles, but that’s not what happened.

Expanding the data sample to the top five European leagues, players born in 1995 still lack competitiveness.

Jose Chiella, who has served as a talent scout for teams such as Sporting Portugal, Porto, and Panathinaikos for over 20 years, said, “I don’t believe in generation gaps,” at least not in terms of talent and quality. He believes that market forces have created such a “disconnect.” He said, “Over the past six or seven years, market-dominant strategies have increasingly been based on different logic. It has increasingly become a trade, a typical American trade culture.”

“Now, teams are not looking for players born before 2000. Everyone is making lists of U23 players, and considering slightly older players feels like making a losing deal. This supply-demand relationship ultimately affects player development.”

As Chiella said, the business model of many teams has shifted towards “training on behalf of others,” cultivating young players and selling them to top teams, which has fundamentally changed the player development model.

According to Transfermarkt data, among the 50 large transfers in the Premier League this summer, only 8 involved players older than 26. Ten years ago, in 2014, among the 25 large transfers, 8 also involved players older than 26. In other words, the market value of players in their twenties is completely different now compared to before.

Real Madrid’s squad that won the Champions League last season consisted of a mix of players born in the 1980s and early 1990s (such as Thibaut Courtois, Dani Carvajal, Nacho, Antonio Rüdiger, David Alaba, Lucas Vázquez, Luka Modrić, and Toni Kroos) and a group of young talents born in the late 1990s and early 2000s (including Fede Valverde, Eduardo Camavinga, Aurélien Tchouaméni, Vinícius Júnior, Rodrygo, and Jude Bellingham).

While this squad appears to have a wide age range, there is a notable absence of players born around 1995 (with the exceptions of Kepa Arrizabalaga born in 1994, Ferland Mendy in 1995, and Dani Ceballos in 1996). This summer, Nacho and Kroos left the Bernabéu, while new additions to the team include Kylian Mbappé (born in 1998) and Endrick (born in 2006).

Barcelona faces a similar situation, with a few players born in the late 1980s (such as Robert Lewandowski) and early 1990s (like Iñigo Martínez and Ter Stegen), along with core players born in the late 1990s. Only three players were born between 1992 and 1998: Andreas Christensen and Raphinha (both born in 1996) and Frenkie de Jong (born in 1997).

Chelsea serves as an extreme example. Their transfer policy in recent years seems to have distanced them from players born before 1997. Last season, apart from Thiago Silva (born in 1984), Raheem Sterling (born in 1994), and Ben Chilwell (born in 1996), many of their core players were born around the turn of the century. Moreover, with the arrival of Maresca, Sterling and Chilwell’s futures at Chelsea look uncertain.

Kiela comments, “The trend of focusing on the talent market transactions is the decisive factor behind this apparent discrepancy. It’s incredibly difficult to find players, within a specific age range—say, between 24 and 30—who fit the profile of someone like Bernardo Silva. More and more teams don’t want to ‘waste time’ working with players over 24 because there’s a commercial logic that suggests players start to lose value from 25 or 26 onwards. Consequently, resources are being directed towards younger players.”

Chelsea is an example of this approach, but there are notable exceptions.

Bayern Munich is one such exception. Their core squad includes Leon Goretzka, Joshua Kimmich, João Palhinha, Serge Gnabry, Leroy Sané, Kingsley Coman, and Kim Min-jae, all born after 1995. Another example is Manchester City, the back-to-back Premier League champions, who have John Stones, Mateo Kovačić, and Bernardo Silva (all born in 1994), along with Nathan Aké, Manuel Akanji, and Jack Grealish (all born in 1995), Rodri (born in 1996), and Rúben Dias (born in 1997).

Joe Davies, who played for Port Vale, Luton Town, Leicester City, and Fleetwood Town before founding a digital marketing company to help professional footballers build their brands, has delved into this issue from both business and sporting perspectives. He says, “Messi and Ronaldo are unique. They have created unrealistic expectations for football superstars. They have redefined the upper limits of what a football superstar can be, overshadowing many incredible players who have emerged since then.”

Joe Davies believes that only when Messi and Ronaldo begin to gradually fade from European football, “will we recognize the talents of players like Erling Haaland and Mbappé. When Messi and Ronaldo were at their peak, everyone else was overlooked.”

As a former professional footballer with a keen understanding of marketing, Joe Davies attributes this to commercial factors and discusses the “immaturity of player brand promotion.” He believes that modern players have far more opportunities to promote themselves, which is one of the reasons why “a new generation of young talents, such as Mbappé, Haaland, Vinícius, Bellingham, Jamal Musiala, and Yamal, have become famous so quickly.”

The term “new wave” fits perfectly. Whether in music, movies, sports, or any other field, we are accustomed to using such vocabulary to describe the phenomenon mentioned above. Sometimes, it takes a band, or an athlete to forcefully break through and pave a new path for others. Sometimes, it’s because people are eager to propel a new star to fame. Other times, people stand on the opposite side, desperately rejecting the spirit that transcends the era and its key figures.

However, apart from image and fame outside the pitch, Joe Davis believes there is another factor driving this “new wave”: subtle changes in the style of play. In his view, it “may be more suitable for players who excel in flashy performances” – or at least players like Erling Haaland and Kylian Mbappé, whose talents are so astonishing that, upon entering the top tier of football, they do not bear as many defensive responsibilities as players born five years earlier.

Joe Davis recalled his experience as a defender at Port Vale when he was 20, facing an 18-year-old Jack Grealish – who was then on loan at Notts County from Manchester City. He said, “He was everywhere. He could cover the wing-back, press our wingers, and even drop back to receive the ball near the byline. Players at that time not only needed talent but also diligence, discipline, and the mindset of ‘don’t let the fans down.’ The same goes for Bernardo Silva, who is not only skilled and intelligent but also excellent in defensive intensity and adaptability.”

“That era – the era when I played – players were instilled with different values during their breakthrough years, which might be why they were more modest, organized, and craftsman-like in their games. This naturally shifted people’s attention from them to more exciting and creative players – those who could immediately capture the attention of ordinary fans.”

This makes perfect sense. This group of players is now in their mid-to-late twenties, and as they prepare to become the backbone of football, the requirements have changed. Nowadays, the football world increasingly emphasizes off-the-ball work – not just ‘tracking back’ but pressing in a more organized manner. In earlier years, the role of traditional center forwards seemed threatened, which might be why, apart from Lautaro Martinez, there are few bona fide strikers in this age group.

There is a strange paradox in football today. Individual adoration has been growing at an unprecedented rate over the past decade – also benefiting from the explosive growth of social media and global brands. Yet, for some time now, individual adoration on the pitch has been diminishing. In the past, top teams might have had only one or two “top-tier” players, but now it’s different. The teams built by Pep Guardiola and Jürgen Klopp are committed to creative football, demanding higher physical fitness and technical-tactical skills from every player. It’s easy to imagine that if Bernardo Silva or Fede Valverde were five years older or younger, they would more likely be deployed as wingers or in the number 10 position rather than as all-around midfielders.

Today, individualism seems to be making a comeback, as does the so-called “protagonist aura.” Kylian Mbappé, Erling Haaland, Vinicius Junior, Jude Bellingham, Jamal Musiala, Yamal… They are encouraged to “be themselves” and play to their maximum strengths – for Mbappé and Haaland, this means maximizing their goal-scoring abilities without being distracted by the team’s pressing tactics.

They are rare, talented players whose performances on the field provide fans with excellent viewing experiences, followed by overwhelming promotion and praise for these two players.

Perhaps things are not as complicated as we think. Perhaps the cultivation of top players is similar to wine. Some vintages are just particularly good, and the reasons are hard to explain.

To put it simply, 1987 belonged to Messi, Benzema, and Suarez; 1992 to Neymar, Salah, Courtois, Son Heung-min, and Mane; 1998 to Mbappé, Osimhen, Arnold, Valverde, and Ødegaard; and 2000 to Haaland, Vinicius Junior, Foden, Alvarez, and Tchouameni.

In comparison, the post-95s players seem ordinary. The most valuable post-95s player in the transfer market is Ollie Watkins, born in 1995. However, his career has not been smooth, playing for Exeter City and Brentford before joining Villa and making his Premier League debut at 25. Among the players born in 1996, James Maddison is second only to Rodri. Approaching 28, he has only represented the England national team seven times and has yet to participate in a Champions League match.

Reviewing the list of Golden Boy award winners is also an interesting endeavor. Early winners included Rooney, Messi, and Fabregas. In the past four selections, the winners were Jude Bellingham, Erling Haaland, and Barcelona’s dual stars Gavi and Pedri. Before that, it was Felix, De Ligt, and Mbappé.

The winners from 2014 to 2016 were Sterling, who played for Liverpool, Martial for Manchester United, and Sanches for Bayern Munich. At that time, they were all exciting talents, but even at their peak, they were never held in as high esteem as young Rooney, Fabregas, or Bellingham, let alone being the “hope of the village” like Mbappé or Messi.

In recent years, the top three list for the Ballon d’Or has rarely included other names. Rashford, Origi, Marquinhos, Coman, and Bellerin have all made the cut, and they did have their moments of brilliance, but ultimately, they failed to fulfill their potential. Their career paths were filled with uncertainties, and they never became the indispensable choices for top teams. Perhaps, in some ways, they never became the “complete players” that everyone wanted to see.

The phenomenon of the “Lost Generation” may be even more pronounced in men’s tennis. Federer, Nadal, and Djokovic have exercised extraordinary dominance, and players of similar age like Andy Murray, Stan Wawrinka, Del Potro, and Marin Cilic have also achieved notable results. However, after them, Dominic Thiem (born in 1993) and Daniil Medvedev (born in 1996) are the only two male tennis players born between 1989 and 2000 who have won Grand Slam titles.

Moreover, the latest ATP rankings show that apart from Djokovic, who is ranked fourth, Bulgarian player Grigor Dimitrov (born in 1991) is the only player born between 1988 and 1995 in the top 20. Carlos Alcaraz (born in 2003) and Jannik Sinner (born in 2001) have already led men’s tennis into the “post-Big Three era”.

In team sports like football, the concept of the “Lost Generation” is certainly much more blurred, as individual performances are difficult to quantify in such sports. This term does not apply to the following situations:

We are discussing a period of around four years;

Every top-level match you watch features high-level players from this age group, among whom Rodri can be regarded as the most influential player in world football over the past three to four years.

However, it seems undisputed that as a whole, the post-95s players once lived in the shadow of their older counterparts and then had their potential glory usurped by younger players. The Ballon d’Or rankings may never tell the whole story, but they help illustrate that among the “big names” of the post-95s generation who have received the most attention and recognition, there is a real lack of distinctive, eye-catching talent.

From another perspective, it is completely normal for the post-95s players to be unable to compete with Messi and Ronaldo, but it is also very strange that this age group has produced almost no top-level goalkeepers, center-backs, wingers, or center forwards. The best players in this age group seem to be seasoned, adaptable “system players” rather than tough-defending, flexible midfield playmakers.

Furthermore, the market seems to be abandoning these post-95s players as the focus has quickly shifted to younger players. The post-95s players, who were originally expected to become the pillars in 2024, now have to worry about fighting for playing time, and some even have to worry about finding a new team that will accept them – especially when the market perceives their salary demands as too high. Adrien Rabiot, 29, is still without a team after leaving Juventus in June (he has now joined Marseille). Memphis Depay, 30, has found himself struggling in Europe and had to move to Brazil. As for Raheem Sterling, 29, if he hadn’t received an olive branch from Arsenal at the last moment of the summer transfer window, his future at Chelsea would still be uncertain.

Although Sterling’s attacking performances have indeed declined in recent seasons, he remains one of the most outstanding players of his age group. Winning the Golden Boy award at Liverpool when he was young, followed by four Premier League titles with Manchester City, boasting 82 appearances for the Three Lions, and several times finishing in the top 20 of the Ballon d’Or rankings, such a resume is enough to surpass more than 90% of the post-95s players.

If his former Manchester City teammate Rodri wins the Ballon d’Or this year, it will signify a transformation in his personal image, playing style, and age. In many ways, Rodri is the most suitable candidate for the Ballon d’Or this year, as he is the most prominent leader among the “lost generation” of the post-95s.

Although Rodri may give a sense of “not showing off” in matches, and although such a Ballon d’Or award may bring a sudden sense of happiness to him, the arrival of such an award can also be seen as a rare opportunity for revelry for the “lost generation” that has been abandoned by football.